Feel free to connect with me on twitter @thepiccledotcom!

Preface

READ: I initiated this write-up at the start of July, and decided not to post it right away, opting to wait for the right moment instead. Sooner than expected, that opportunity may be now. Three days ago, Financial Times published a piece about UMG and Deezer’s new payout model - one which is ultimately in favor of big labels.

As you will learn in this in-depth (sorry) write-up, the current payout model from streaming-providers to is not sustainable for big labels in the long term. However, recent developments suggest that this is going to change - one of the catalysts I expect to trigger a re-rate.

In the “prior” payout structure, subscription fees from listeners are combined into a “royalty pool”, which is then distributed among copyright owners according to their proportion of total streams. Royalties are the same regardless of who created the song or whether the song was listened to passively via an algorithm or if users actively searched for it. In a world where it has never been easier to upload music (>100.000 songs uploaded to Spotify daily), it is quite clear that big labels are losing share by the minute unless they manage to counter the dilution by uploading a lot tracks daily (they don’t).

In the new “artist-centric” set-up from Deezer, the following aspects are integrated to the above model:

Artists categorized as professionals (defined as those who accumulate no less than 1,000 streams per month from a minimum of 500 unique listeners) will enjoy a "double boost." This means that each stream they receive will count as two streams in the overall "royalty pool."

Songs that fans actively engage with (i.e. search for inside the app vs. algorithm-driven) will also receive a “double-boost”. Hence, if you search for Money In the Grave by Drake, and listen to the song for more than 30 seconds, it will count as four (4) streams.

Aside from the above, Deezer will demonetize non-artist noise audio (i.e. sound of rain, wind, or similar), as well as do more efforts to tackle fraud - i.e. song-leaks, AI-songs, etc. The new model will be trialed in France as of Q4-23, with a subsequent roll-out in other markets.

While the Deezer-agreement is not a huge value-trigger by itself, it signals that UMG is experiencing progress in its dialogue with streaming providers. If a remotely similar deal is landed with Spotify over the coming year(s), we are looking into a complete re-rate of all music-related companies.

Introduction

Since the rise of the internet and peer-to-peer file-sharing platforms (i.e., Napster) in the late 1990s and 2000s, the music industry has been in a seismic shift toward digital consumption. Shifting away from vinyl records, cassettes, CDs, and later digital optical discs like DVDs, 67% of global music consumption is now consumed via the internet. Zooming in on the developed world this figure is closer to 80-85%.

On a related note, it has never been easier for upcoming artists to produce and distribute their own music. Access to music production and consumption has truly been democratized, and big music labels - such as Universal Music Group, Warner Music, and Sony - no longer act as the gatekeepers of music. Not so fast... In this write-up I share my rationale for investing in Universal Music Group.

Background

Universal Music Group (UMG) is the world’s leading music company with a global market share of 32% in recorded music, and the runner-up position in music publishing with a 21% market share. In fact, 4/5 of the most streamed artists on Spotify in 2022 are signed with UMG, underpinning its dominant market position. Adding to this, UMG had writer-interests in 9/10 of the most-streamed songs on Apple Music.

In October 2021, the company went public via an IPO on Amsterdam’s Euronext exchange. Prior to this point, the company was owned by French media conglomerate, Vivendi, whose shareholders had been pushing for a spin-off for several years. Leading up to the IPO, Vivendi had already divested 20% to Tencent and 10% to Pershing Square (through Ackman’s SPAC). As such, the IPO essentially consisted of a 60% spin-off of UMG to Vivendi’s shareholders, leaving Vivendi with the remaining 10% stake in the listed entity.

Tencent bought in at an EV of €30bn, and Pershing Square at an EV€35bn (NIBL of 2bn, hence implied equity value of €33bn). Today, shares trade at 23.5 equal to an equity value of €42.824bn

According to Capital IQ, it does not seem like any major changes to the ownership structure has happened since then.

Company description

Listed in Amsterdam, Universal Music Group (UMG) is the world leader in music-based entertainment. With >220 artists, >3 million recordings, >4 million owned and administered titles across its plethora of labels, which cover virtually any genre, UMG is one of the three major players in the music-label industry, alongside Sony Music and Warner Music Group. Its catalogue of artists include the likes of Taylor Swift, The Weeknd, Drake, and Billie Eilish. Adding to this, UMG also has ownership rights to deceased/retired artists, such as Elvis Presley, Amy Winehouse, Sting, and many more whose music is still listened to millions of times per month.

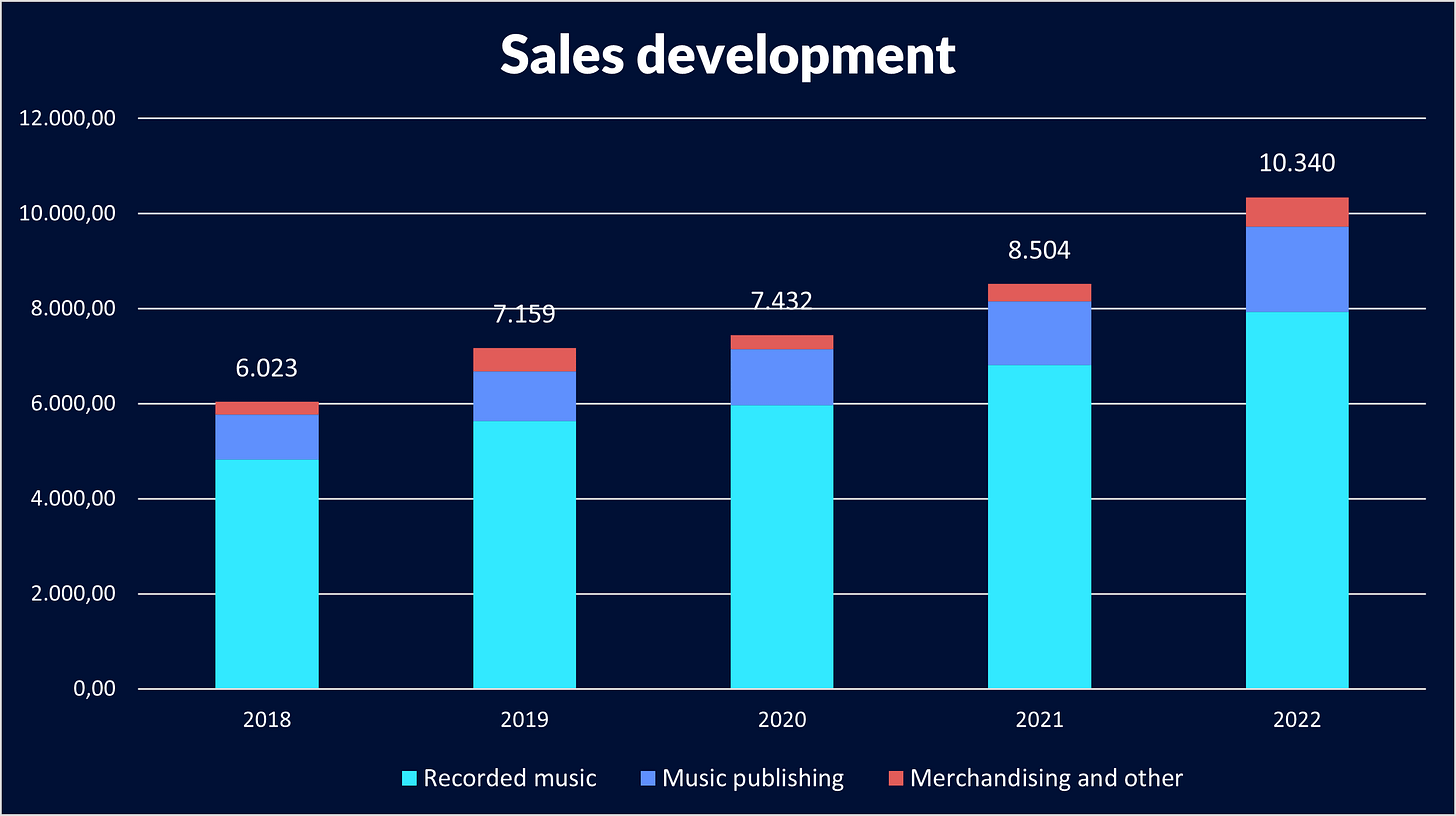

The company’s operations are divided into three segments; Recorded Music (77% of LTM sales), Music Publishing (17%), and Merchandising (6%).

Recorded Music

The Recorded Music business focuses on discovering and developing artists, as well as marketing, distributing, selling and licensing artists’ work. Artists’ audio (songs) and audiovisual (films and documentaries) work are owned and copy-right-administered by UMG. Sales are generated from music streaming/subscription platforms (I.e., Spotify, Youtube, Apple, Amazon), sale of CDs/vinyl records, as well as sales licensing agreements in video games, TV-production, and more.

UMG operates with a multi-level label structure, each of which has its own niche market and competitive advantages. This structure enables UMG to capture a broad array of genres and styles as well as fostering a healthy level of competition among the labels - which in turn improves quality, productivity, and innovation.

Music Publishing

The Music Publishing segment focuses on managing and monetizing the musical compositions created by songwriters/composers. Hence, this segment deals with the administrative aspects of copy-righting songs, collecting and claiming royalties as well as pitching said songs to be included in sound recordings, films, television, advertisements, video games, concerts, etc. In return for these services, UMG collects a share of the royalty rate before paying the songwriter/composer.

This segment also cover the acquisition of catalogs - such as when UMG acquired Sting’s career catalog in Feb-22.

On the surface, it can be difficult to differ between the two segments, however, once you grasp the difference, it is relatively straight forward. For every recorded song, there are two IP rights to consider - each of which can be licensed, sold, assigned, and utilized in various ways by its respective owners. The first IP-asset, represented by publishing companies, concerns the copyright on the composition itself - the lyrics and melody that make up the song. This is also commonly referred to as “sheet” music given that it can be written with letters or notes onto a sheet of paper. The second IP-asset is the copyright pertaining to the specific recording, which is also referred to as the “master”. Bear in mind that the right to a master is limited to that specific recording, hence the same song performed by two different artists may have two different owners - and thus may be exploited and licensed separately. This also explains why Tayor Swift re-released her albums (“Taylor’s version”) with new vocals, creating new masters and thus quasi-regained control of her catalogue.

Merchandising

Operated through the Bravado brand, the merchandising segment aims to capitalize on UMGs >220 artists’ fan-base by offering artists access to its end-to-end merchandising ecosystem, covering the design, production, and distribution of artists’ merchandise. Such products include apparel and accessories, toys, games, luxury goods, etc., and are sold at venues/live-shows, through ecommerce stores and select retail outlets.

Industry dynamics

The past- and future success of any label, UMG included, relies on its ability to discover, partner with, and introduce new artists, writers, and composers to the music-scene, and help them achieve their greatest creative and commercial potential. This has become much more challenging given the sheer volume of new songs introduced to the marketplace, thickening the layer of noise that artists and labels alike must penetrate to capture audience’s attention. In fact, Spotify’s library is growing >100.000 every day, and has gone from ~1 million songs in 2009 to >100 million in 2023. Adding to this, UMG recently pointed out that >90% of new uploads have less than 1,000 monthly listeners. Knowing this, it is easy to understand why most artists see themselves signed to a label company even if the desire to be an independent artist. After all, the labels’ extensive network, deep industry knowledge, data, and vast amounts of capital is key to launch a successful career in the music industry. According to RIAA, it can cost upwards of $2 million to break a new artists in a major market - hardly something a non-supported upcoming artist can finance.

The increased costs brought by the increased competition/noise is, however, offset by the fact that labels can now take less risk with a new artist. This is because new releases no longer have to be in an album format as was the case with physically consumed music. Now, labels can adopt a wait-and-see approach where an artists can prove him/herself by releasing 1-3 singles before signing on a larger deal. This is key given the industry’s shared characteristics with Venture Capital in that 1/10 artists become a success - but the ones that are successful make up for all of the failures. Similarly, labels have gained access to unprecedented amounts of data, useful to gauge listeners’ pattern of interaction, demand, etc.

Having established this, the pace at which the new/noisy content is uploaded to streaming platforms is critical as labels’ share of the total streams get diluted over time. This is problematic as because labels are compensated based on their share of total streams. Hence big-label-artists must yield ever-higher streams to offset the effects from the vast amounts of releases uploaded to the platform, albeit the majority of these have >1,000 monthly listeners.

“What’s become clear to us and to so many artists and songwriters—developing and established ones alike—is that the economic model for streaming needs to evolve. As technology advances and platforms evolve, it’s not surprising that there’s also a need for business model innovation to keep pace with change” - Lucian Grainge, CEO of UMG.

One can only speculate how this is going to be resolved. The recent agreement with Deezer (covered in the preface) may be one option to resolve such issues. However, I think it is fair to expect some variance between the label-and-platform agreements, especially with larger players like Spotify. Adding to this, platforms are asked to increase its focus on solving “digital trappers" (stream farms and bots), which further distorts the distribution of streaming revenues.

The shift to streaming also means that the business model has evolved from a traditional inventory turnover-driven business into an asset-light and annuity-like recurring revenue business. Additionally, the CAC costs are now more or less shared between labels and streaming-providers compared to when labels controlled the entire value-chain. This, coupled with the fact that music is non-cyclical, non-seasonal, and consumed by virtually anyone creates a resilience which is hard to compare with anything else other than food and other necessities.

“Music thrives at the intersection of culture, technology, and commerce. It’s the single most influential global art form, with an unmatched ability to attract audiences, drive social interaction, transcend borders, and unite people” - Robert Kyncl, CEO Warner Music.

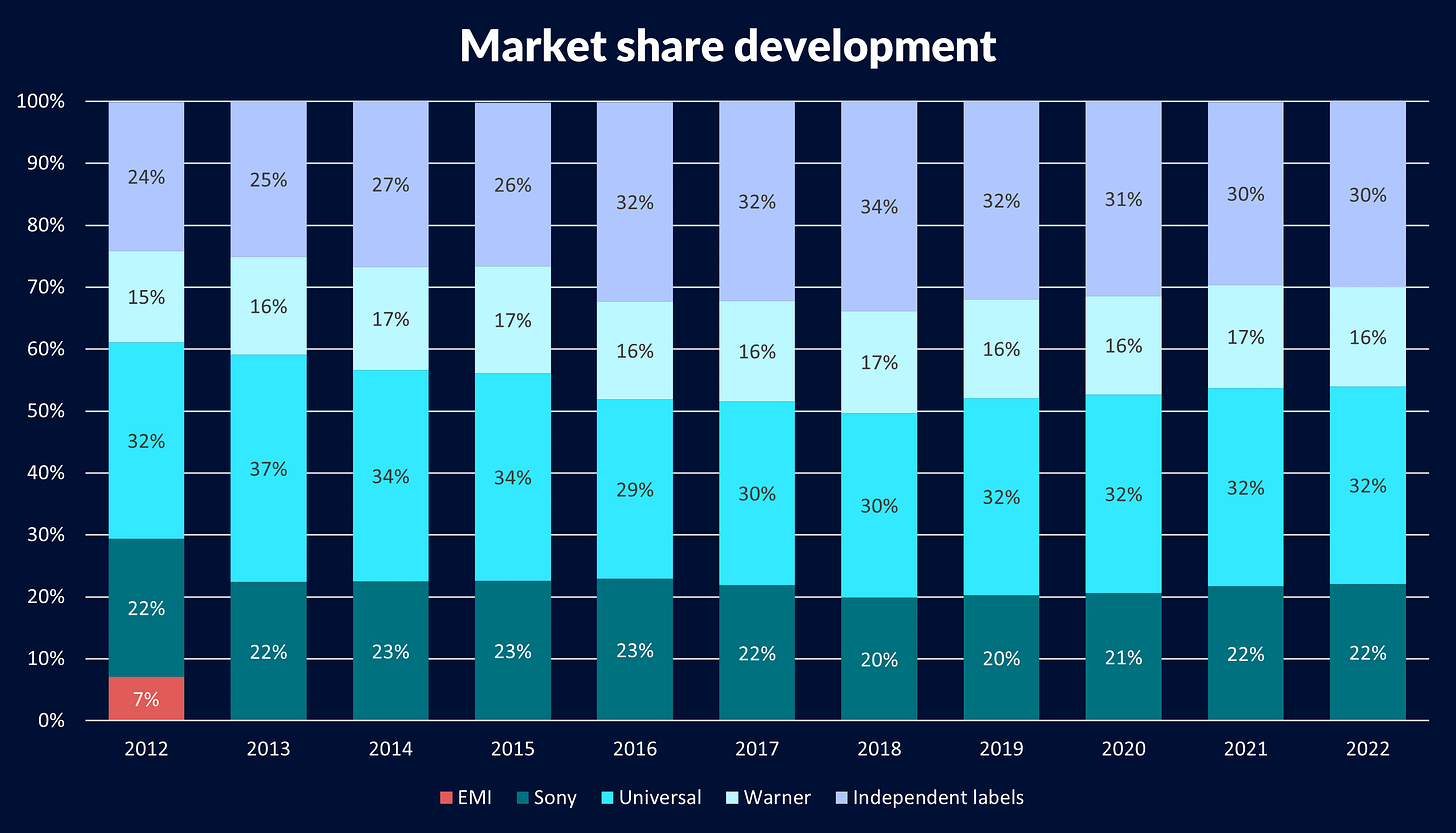

The music industry is dominated by three big labels, namely, Universal Music Group (32% market share), Sony Music (22%), and Warner Music Group (16%), with the remaining 30% split among a series of independent labels. This stable competitive environment existed even before the streaming era and is unlikely to change materially anytime soon. Interestingly, though, UMG lost ~8pp. market share from FY13 to FY16, but has since bounced back. That said, at no point did they lose their leading position.

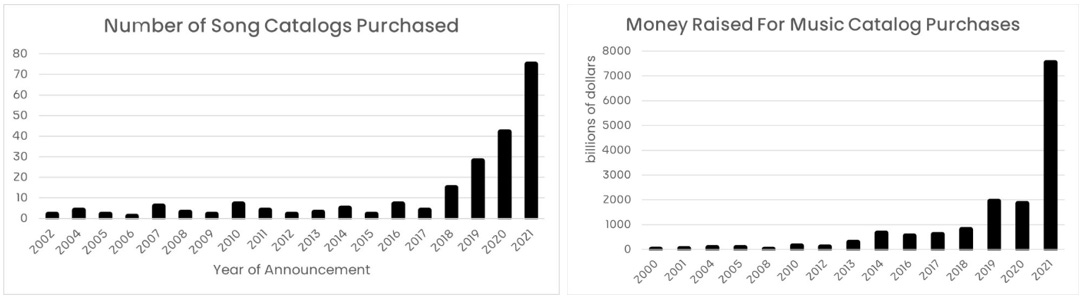

As mentioned earlier, the digital nature of music consumption has reduced the risk that labels take when betting on an upcoming artist’s success. The flip-side of this is that the reward from a successful artist is similarly reduced. This is particularly relevant when looking at the contractual agreements made with said artists. In the past, contracts usually spanned over several years (+10), and labels owned everythinh the artist produced into perpetuity. However, this is much more complicated today where artists are usually signed for a shorter period of time (~5 years), and contracts contain a “reversion” clause where artists regain the rights to their music a number of years after contract-end - commonly ~5 years. While most releases receive the most amount of streams within 3 years, it is nonetheless a less favorable set of circumstances than historically. To keep these rights, labels may renegotiate with the artist upon termination - and one must expect that labels know how much a catalog is worth given data they have at their disposal in this day and age - hence, the risk of overpaying is probably not too high. Labels are not the only buyers of such catalogues, evidenced by the rising number of catalogue-deals completed by non-label buyers, such as the Hipgnosis Songs Fund (listed on LSE) - backed by Blackstone - and Chord Music Partners - backed by KKR. In other words, serious money is being poured into the catalogue-aspect of the industry.

While there are many positive attributes to such catalogues, the risk of overpaying is still inherently present. This is evident in the financial statements of Hipgnosis who have masked its actual (poor) performance with frequent acquisitions. The spending-spree has now come to a stop as there is no more money left - and tapping the equity market at current (near all-time-lows) seems unlikely. Hence, we should soon see what level of cash generation catalogues can deliver. In fact, Barclays find that Hipgnosis Music Fund ($SONG), Reservoir Media ($RSVR), and Round Hill Music Royalty Fund ($RHM) generate 3.5-5.5% post-tax ROIs on catalogue acquisitions. That said, if the Deezer payout-model becomes the standard, $SONG may generate wildly different cash flows than what the market initially anticipated.

Circling back to the cash flow aspect of the industry, there are broadly three ways in which the music is monetized:

Subscriber-based royalties: The cash flow generated from streaming platform’s (“DSPs”) paid subscribers. As alluded to earlier, the current payout model compensate labels on a pro-rata basis, based on their share of total streams. I think Pershing Square illustrated the dynamics quite well in their investor presentation om UMG:

From this it is clear that the success of labels is dependent on 1) DSPs pricing (ARPU) and 2) Labels’ share of total streams. The higher each of these components are, the better for the label. Hence, ceteris paribus, when Spotify hike its prices, it is good news for labels and artists. While DSPs decide on retail pricing themselves, they are likely influenced by the pressure coming from big labels who, together, account for ~70% of total streams. Individual artists have limited say in this regard as no single artist account for more than ~2% of total streams, and thus they have limited bargaining power. Also, for most artists, streaming is top-of-funnel with the end goal of converting listeners into a concert-attendees.

Ad-based royalties: The freemium model that most DSPs are using makes you listen/see ads before a given song is played. In such instances, labels collect a percentage of the ad-revenue generated. Note that this does not include songs played on radio where neither the label or the artist gets compensated.

Adjacent opportunities: This includes merchandising, gaming, and other ways in which the artist and labels can monetize the artists’ work and their brand.

Market assumptions

As depicted in the first graph of this write-up, streaming has single-handedly turned around the music industry’s downward trajectory. Therefore, it makes most sense to base the valuation on the adoption of streaming. Albeit the developed markets have been responsible for most growth up until now, there is plenty of room for streaming to gain further foothold on a global level as emerging markets start to convert to streaming too. In fact, that is exactly what we are seeing play out.

The penetration-rate for streaming is much higher in developed markets, particularly in the Nordics where 9/10 are music-streamers, using an average of 3.2 hours/day listening to music. Intriguingly, freemium users spend 40 minutes (avg.) more time listening to music than paid subscribers in this region, and 53% are paid subscribers. As such, there is further room to grow even in the most mature market. On a similar note, Americans still consume much of its music via radio (44% of all U.S music listening hours), which does not currently compensate neither artists nor labels. By monetizing radio (i.e., via talks with legislators) additional growth in developed markets may be unlocked. All this is to say that music streaming in the developed market still has room to grow. Another point to add is that up until recently DSPs have refrained from raising prices for the better half of a decade, whereas subscription video-based streaming providers increased prices almost every year. In other words, music is relatively under-monetized.

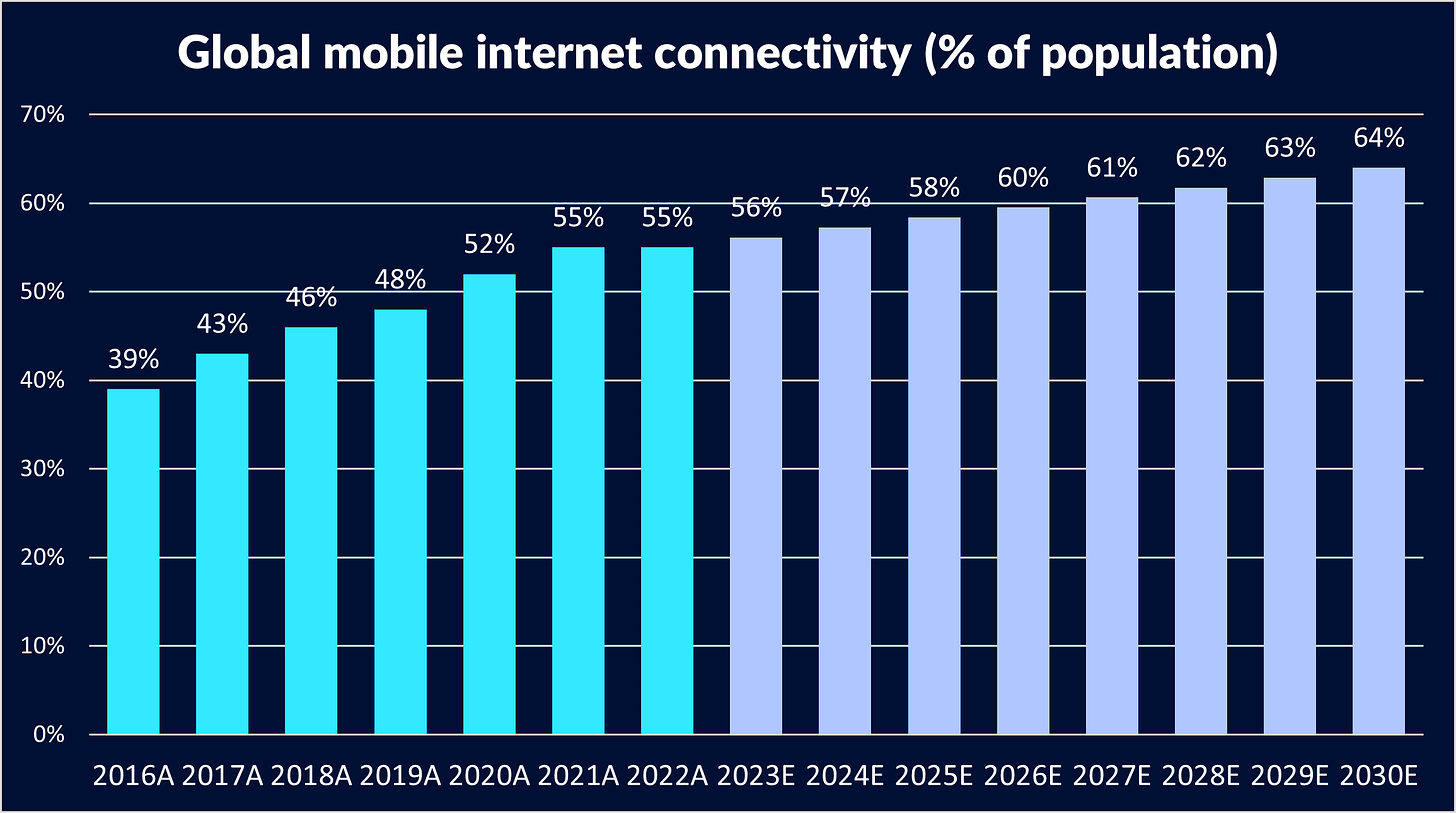

As for emerging markets, streaming is still in its beginning stages and thus growing at rapid pace. A prerequisite for streaming to be widely adopted is 1) reliable access/connection to the internet, 2) adoption of smartphones, and 3) price. Starting with the latter; as smartphone affordability improves and DSPs are competing on price, this issue should not be pose a barrier in terms of adoption-rates However, if DSPs opt for aggressive regional ARPU cuts, this will undoubtedly affect labels negatively - something to keep in mind. In general, I think it is logical to expect the penetration rate of streaming to grow in tandem, albeit at a slower pace, with the adoption of smartphones and implementation of reliable internet connectivity.

Most detailed market-reports cost more than I am willing to pay, and thus I will keep the forecasts on a global level. Ideally, I would have forecasted the development of smartphone/internet and streaming penetration on a regional basis, and then add an forecasted ARPU layer on top of it. A similar approach is used by Pershing Square in their presentation of UMG. Below is an example:

However, when I try to reconciliate the global smartphone penetration rate with other sources (GSMA and Statista), it seems the numbers provided in the above table is significantly lower. According to both GSMA and Statista, the smartphone penetration rate has been >65% since 2016.

As outlined earlier, smartphone adoption is only one prerequisite of higher streaming penetration rate - internet access is another crucial factor. GSMA forecasts that the global mobile internet users will reach 64% by 2030:

I will assume that the internet connectivity is reliable enough for music streaming for 90-95% of the global mobile internet connectivity. Additionally, I will subtract all >65 year-olds from the addressable population.

Returning to the three-fold music monetization areas: 1) Subscriber-based streaming, 2) Ad-based streaming, and 3) Adjacent opportunities.

Subscriber-based streaming (paid streaming)

According to several sources, Spotify holds a global market share of ~30%, and has 220m paying subscribers (Q2-23). Using this metric, there must be ~733m paid subscribers globally, equal to ~10% of the global population. However, adjusting for lack of mobile internet penetration rates and people aged >65 years, the number is closer to ~22%. Here is a bridge for 2023 (for reference):

Going forward, I expect paid streaming to reach 40% of the applicable user TAM, equivalent to 18% of the forecasted global population. I think this is a sensible base-case considering it took ~10 years to reach ~10% global penetration of music-streaming (~35% in developed markets).

Next-up is assessing the ARPU development. For this, I am using Statista estimates alongside my own projections (from ‘28-’30). DSPs way to gain share is to compete on price and slowly increase those prices as they gain foothold and the market matures. That translates into a low ARPU in the first ~5 years before prices are hiked. This explains the more or less flat ARPU assumption. Multiplying ARPU by the total number of paid subscribers equals the projected market-size of subscriber-based streaming:

As streaming is adopted in the emerging markets, I expect competition to be fiercer. This is because the neither UMG, Sony, or WMG have a strong presence in these countries. For reference, more than 80% of UMGs revenue is generated in developed markets. While this labels with gravitate toward these markets naturally, I think it is naïve to think that labels, such as Saregama and Tips (both Indian-listed), are not going to go head-to-head with the big guys on their home turf. That said, developed markets still have a lot of growth left, potentially amplified by an improved payout model across all platform. The uncertainty about the new payout model obviously adds a layer of uncertainty to the subscription-based forecast. However, I still assume a return to ~33% market share for UMG:

Ad-based streaming

Having done much of the ground-work in the section above, this section is going to me much simpler. Since music is consumed by virtually anyone, I will assume that proportion of the applicable population (defined above) that not paid subscribers will listen to music through ad-based streaming. Most sources point to an annual ARPU of $1/user. However, with the increasing attention toward proper monetization of music, I think it is acceptable to assume a $0,15 ARPU increase over the coming seven years. As such, the ad-based streaming assumptions can be summarized as follows:

One could argue that it is perhaps too pessimistic to assume a declining user-base over the coming years, especially considering that this is by far the most economical option of any sort of entertainment for end-users. However, this is just a result of the higher assumed conversion rates for paid streaming which may be too optimistic. Additionally, this effect is magnified by the decision to keep >65 year-olds out of the applicable user-base in a world where a this exact group is making up a growing proportion of the global population.

Adjacent opportunities

This is kind of a black box - only limited by imagination. Essentially, it comes down to labels’ ability to monetize existing and new formats - i.e., social media, NFTs, digital fitness, and gaming. This is particularly interesting when considering that TikTok paid the music industry less than Peloton, according to Goldman Sachs’ music in the air report.

Due to the high levels of uncertainty and the many possible verticals associated with this segment, I will refrain from incorporating it into this segment, and incorporate it into the valuation section.

Financial analysis of UMG

Having established the industry dynamics and the high-level future projections, this section aims to understand the UMGs financial development. These findings will also serve as benchmarks for the company-specific forecasts.

Perhaps an odd starting point, however, useful for the valuation in the subsequent section, UMG holds ownership in:

Spotify (6.487 shares x 155.47 = €860.15m)

Tencent Music Entertainment (12.246 shares x 6.63 = €72.77m)

VEVO LLC (€74m)

To get at cleaner look into the performance - and value - og UMG, the effects that these investments have on the financial results will be adjusted accordingly.

Generally, it has not been easy to get a full grasp of the financial performance. Complicated by, among others, the above ownership stakes, the industry accounting, and the fact that data prior to 2021 has been retrieved from the prospectus which uses a slightly different wording/recognition of items. I could have made life a little bit more miserable by retrieving data from UMGs performance under Vivendi’s ownership, however, I decided against it as I think data from 2018 and onwards is sufficient for the purpose of this section.

UMGs performance across all segments have been stellar, with double-digit CAGR (13.3%) from FY18-FY22. Even during covid, UMG managed to grow its top-line - a testament to the resiliency/non-cyclical business model. Below is an overview of the segmented and consolidated performance:

The company recently posted its H1 results, beating analysts’ estimates across the board. On an LTM-basis, sales amount to €10,754m with approximately the same sales-mix as depicted above. From a profitability standpoint, the business is also in great shape, with consistent EBIT margins of ~18-20% on a normalized basis. Generally, the management tends to use adjusted EBIT(DA) quite a lot when presenting their numbers, and it is sometimes difficult to reconcile adjusted and reported numbers. Also, adjustments tend to include “one-time items” which appear to be recurring over the entire period (i.e. restructuring costs).

The Music Publishing segment is the more profitable segment (logically as there are limited A&R costs associated with this segment), closely followed by Recorded Music. The overall performance for these two segments are closely correlated given the cross-over of artists/composers represented in these segments. Precisely because of this relationship, most catalogue acquisitions introduce cost-synergies with limited top-line impact. The top-line will only be affected in instances where the acquired catalogue is created entirely independent of UMG. As for the last segment, Merchandising, margins are quite thin at ~4-5%. However, we have yet to see how labels are going to monetize on artists’ fanbase in more innovative (and likely cost-efficient) ways.

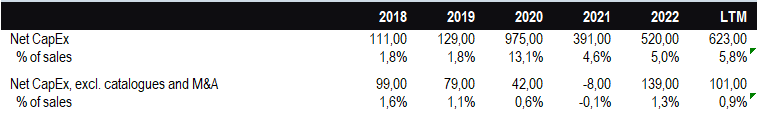

The business model demonstrates great cash generation, primarily attributable to the aforementioned margins together with the minimal investments needed for efficient operations. Notably, UMG benefits from working capital benefits as it receives royalties from its customers (i.e., DSPs) before compensating artists with a delay. Adding to this, the maintenance CapEx is slim to non-existent given the long life of the music assets:

That said, the hits for the coming decades are yet to be made, and thus UMG must continuously find new talent - a counter-argument to the abovementioned notion about the maintenance CapEx. However, given the nature of the industry it is incredibly difficult to assess what such level should be. Below is an overview of CapEx with and without investments in catalogues + M&A:

The sum of the above trickles down to a solid FCF margin of 10-12% on an unadjusted basis. Using the “normalized CapEx” figure shown above, the margin runs at ~15%.

Looking at ROIC, the story is similar. UMG comfortably generates double-digit ROICs. That said, the ROIC has trended down since 2018 which is obviously not preferred. This is driven by a lower invested capital turnover:

Again, due to the nature of the business, it is difficult to assess when investments (signings + catalogues) have recouped their investment costs. It may take a one year or never at all. Interestingly, though, the decline in ROIC coincides with the large catalogue investments:

Thankfully, the management has been vocal about its investments in catalogues, explaining that it is not core to their growth journey.

As mentioned earlier, it is easy to overpay - even for some of the most iconic catalogues, magnified by the increased competition for such assets, and I think the management recognizes that. Thus, I do think UMG will still acquire catalogues strategically, but I don’t think we will see 2020-levels anytime soon. I could be dead wrong about that though.

Some general comments that I note is that UMG has incredibly low levels of debt - albeit growing. Trading at less than 2x NIBD/EBITDA in light of the high financial visibility is remarkably low, and I fully expect the company to add leverage over the coming years. Something to keep in mind when building the model.

With dividends, the total shareholder return equals index 103. In other words, the performance has been… meh.

Valuation (DCF)

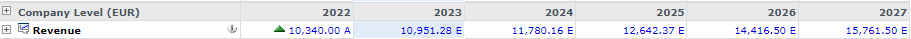

Since most of the recorded music industry development has been built in one of the prior sections, the revenue model is relatively straight-forward:

By comparison, consensus estimates are slightly more optimistic than I am:

In terms of profitability, I assume a slight improvement in adjusted EBIT margins from 18.5% to 20%. In the short-term margins may be compressed a little bit by the higher cost of fan-based monetization products - i.e. a sales-mix tilted more toward Merchandising. Offsetting this, though, the improved streaming payout is not associated with any real incremental cost increase, and thus the higher sales trickles down to adj. EBIT. The latter point may even suggest a slightly higher margin in the outer years is justified.

I expect the company continue to leverage its balance sheet, and thus reap benefits of tax shield and lowering cost of capital. D&A, CapEx, and changes in NWC remains flat at 3.3%, -3.0%, and 1.5% of sales, respectively - and in line with with historical levels. For the terminal period, I slap a multiple of 17x NOPAT which may seem high, but is slightly lower than historical levels (and in the low end of catalogue acquisition’s implied multiples), and I think it is justified given the type of industry we are looking at. WACC is estimated using a target capital structure of D/EV of 25%, resulting in 8.80%.

Lastly, we must not forget UMGs minority ownership stake in Spotify, Tencent Music Entertainment, and VEVO. Taken together, I land at ~€32/share, representing an upside of 37%. Had I instead assumed a RONIC of 35% and TGR of 3.5%, the output is ~€23/share, however, I would have to model further out into the future (steady state) for me to rely on the latter method. In other words, I believe the stock should trade closer to €30.

Exposure to UMG can be obtained both directly (through the $UMG ticker) or indirectly (through Bolloré ($BOL) or Pershing Square ($PSH). If you choose the latter option, you may get a solid discount, however, you also have to factor in the other holdings. Andrew Brown from East72 has made a thorough analysis of Bolloré and its confusing structure in his Q2-23 investor letter - I suggest you take a read. While I do like the idea (and rationale) of owning UMG through Bolloré, I prefer to own it directly.

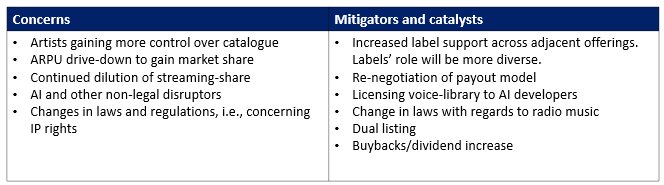

Concerns/mitigating factors

Couldn’t find a place to fit this graphic, but I didn’t want to leave it out. It is evident that people love music they know.

Hey Man great article. Can you walk me through how you got your 2.519 billion for ad based streaming?